Comparison between ALEPlot and ale packages

Chitu Okoli

April 9, 2025

Source:vignettes/articles/ale-ALEPlot.Rmd

ale-ALEPlot.RmdThe ALEPlot

package is the reference implementation of the brilliant idea of

accumulated local effects (ALE) by Daniel Apley and Jingyu Zhu doi:10.1111/rssb.12377.

However, it has not been updated since 2018. The ale package

rewrites and extends the original base work.

In developing the ale package, we must ensure that we

correctly implement the original ALE algorithm while extending it.

Indeed, some permanent unit tests call {ALEPlot} to make

sure that ale provides identical results for identical

inputs. We thought that presenting some of these comparisons as a

vignette might be helpful. We focus here on the examples

from the ALEPlot package so that results are directly

comparable.

Other than its extensions for ALE-based

statistics, here are some of the main points in which

ale differs from {ALEPlot} where it provides

otherwise similar functionality:

- It uses ggplot2 instead of base R graphics. We

consider

ggplot2to be a more modern and versatile graphics system. - Rather than automatically printing the plot to the screen when the

main function

ALEPlot::ALEPlot()is called, theplot()method for S7ALEobjects saves plots as a special S7ALEPlotsobject. As we show, this lets the user manipulate the plots more flexibly. - In the plot, the y outcome variable is displayed by default

on its full absolute scale, centred on the median or mean, not on a

scale relative to zero. (This option can be controlled with the

ale_centreargument toplot(), as we demonstrate.) We believe that median-centring makes plots more easily interpretable. - In addition, there are numerous design choices to simplify the function interface based on tidyverse design principles.

One notable difference between the two packages is that the

ale package does not and will not implement partial

dependency plots (PDP). The package is focused exclusively on

accumulated local effects (ALE); users who need PDPs may use

{ALEPlot} or other implementations.

In each section here, we cover an example from {ALEPlot}

and then reimplement it with ale.

We begin by loading the necessary libraries.

library(dplyr)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'dplyr'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> filter, lag

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> intersect, setdiff, setequal, unionSimulated data with numeric outcomes (ALEPlot Example 2)

We begin with the second code example directly from the

{ALEPlot} package. (We skip the first example because it is

a subset of the second, simply without interactions.) Here is the code

from the example to create a simulated dataset and train a neural

network on it:

## R code for Example 2

## Load relevant packages

library(ALEPlot)

## Generate some data and fit a neural network supervised learning model

set.seed(0) # not in the original, but added for reproducibility

n = 5000

x1 <- runif(n, min = 0, max = 1)

x2 <- runif(n, min = 0, max = 1)

x3 <- runif(n, min = 0, max = 1)

x4 <- runif(n, min = 0, max = 1)

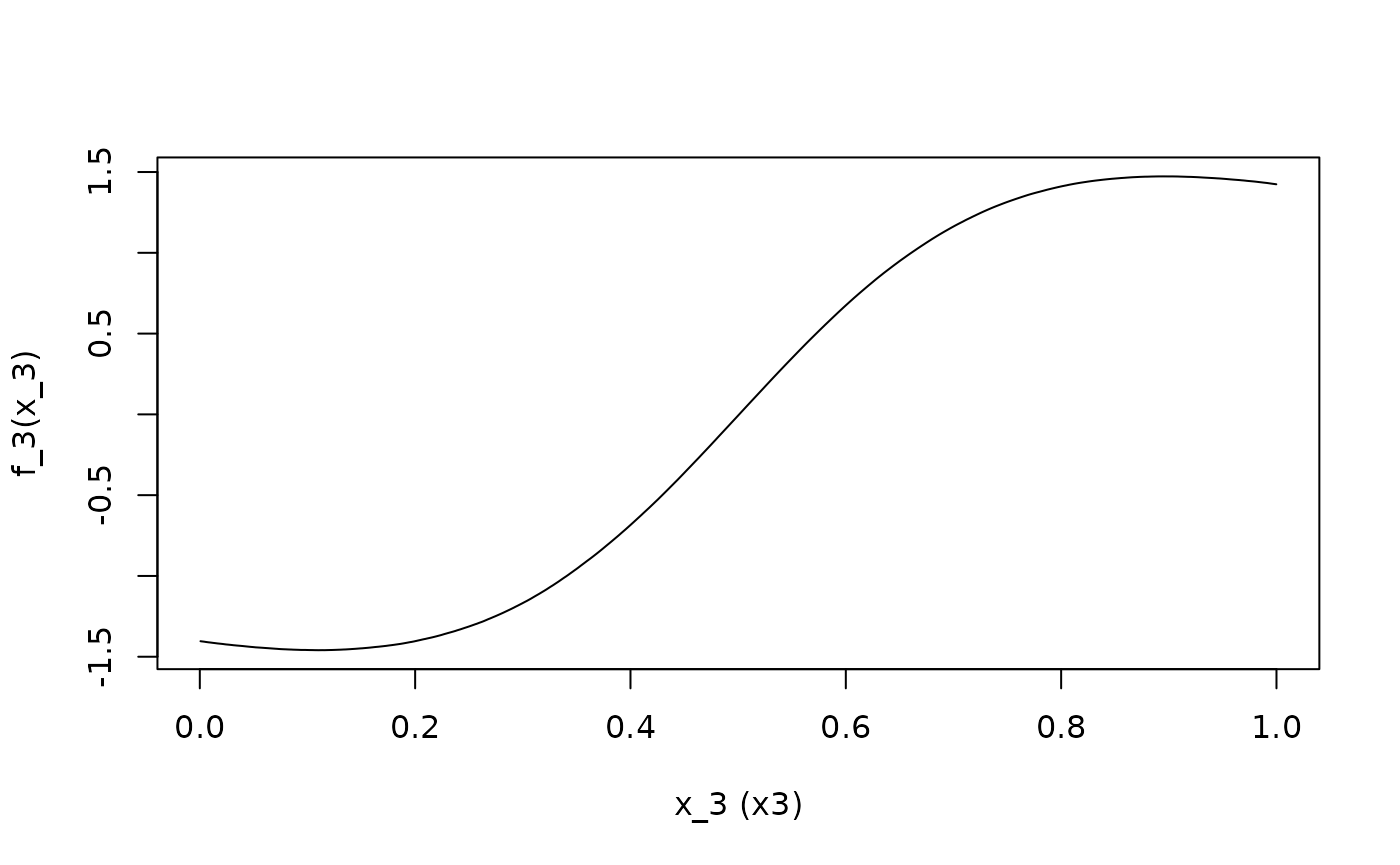

y = 4*x1 + 3.87*x2^2 + 2.97*exp(-5+10*x3)/(1+exp(-5+10*x3))+

13.86*(x1-0.5)*(x2-0.5)+ rnorm(n, 0, 1)

DAT <- data.frame(y, x1, x2, x3, x4)

nnet.DAT <- nnet::nnet(

y~., data = DAT, linout = T, skip = F, size = 6,

decay = 0.1, maxit = 1000, trace = F

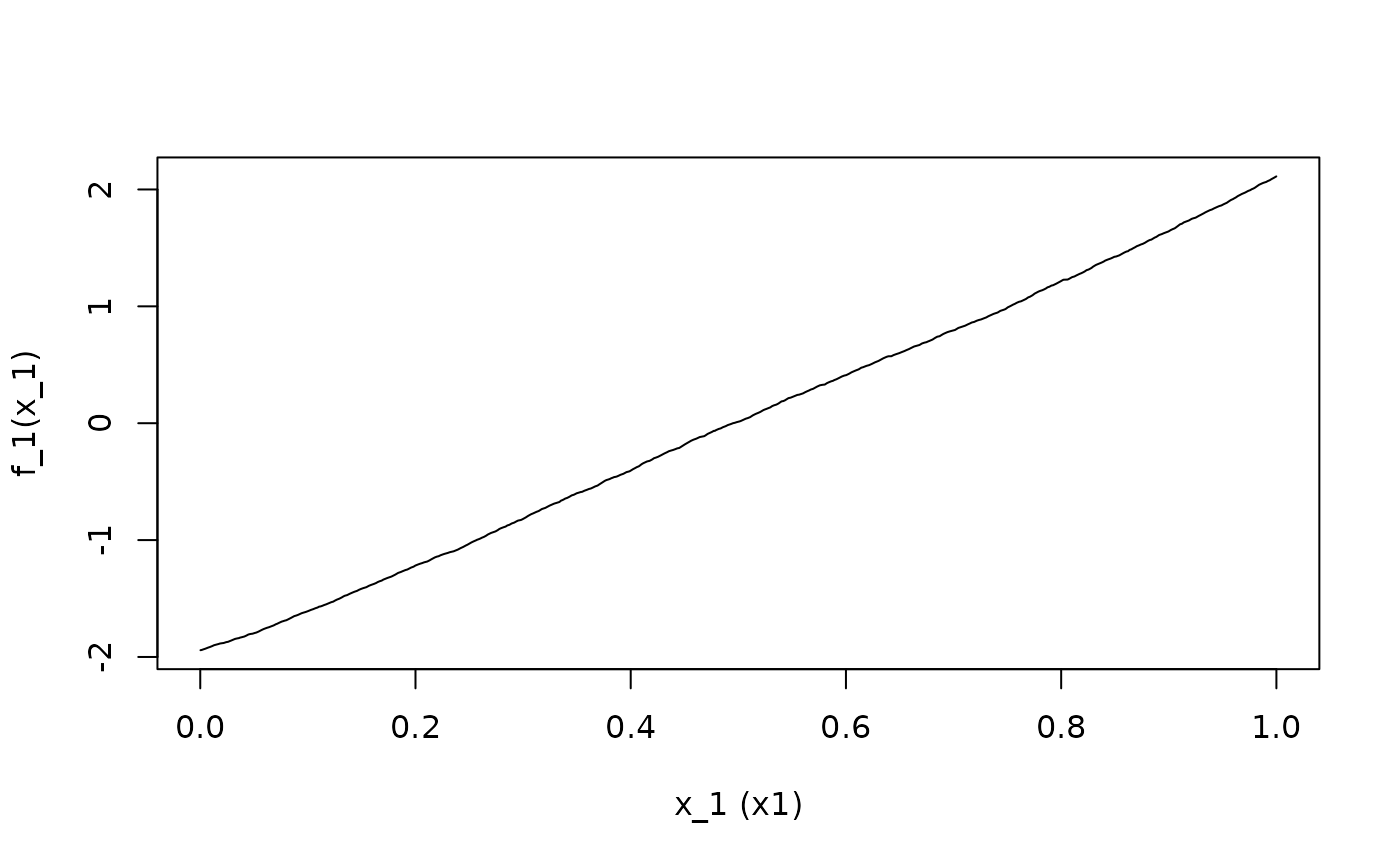

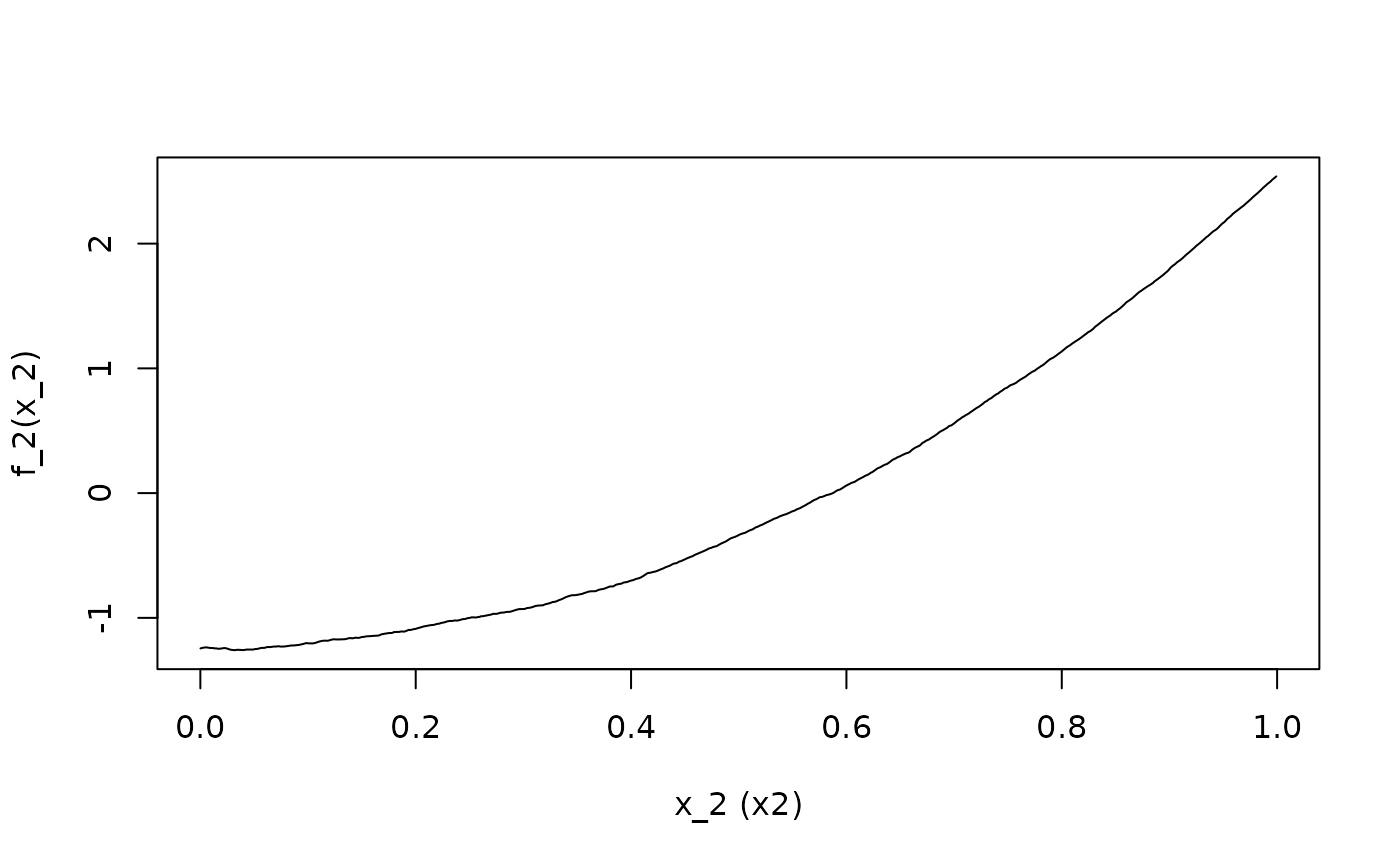

)For the demonstration, x1 has a linear relationship with

y, x2 and x3 have non-linear

relationships, and x4 is a random variable with no

relationship with y. x1 and x2

interact with each other in their relationship with y.

ALEPlot code

To create ALE data and plots, {ALEPlot} requires the

creation of a custom prediction function:

## Define the predictive function

yhat <- function(X.model, newdata) as.numeric(predict(X.model, newdata, type = "raw"))Now the {ALEPlot} function can be called to create the

ALE data and plot it. The function returns a specially formatted list

with the ALE data; it can be saved for subsequent custom plotting.

## Calculate and plot the ALE main effects of x1, x2, x3, and x4

ALE.1 <- ALEPlot(

DAT[,2:5], nnet.DAT, pred.fun = yhat, J = 1, K = 500, NA.plot = TRUE

)

ALE.2 <- ALEPlot(

DAT[,2:5], nnet.DAT, pred.fun = yhat, J = 2, K = 500, NA.plot = TRUE

)

ALE.3 <- ALEPlot(

DAT[,2:5], nnet.DAT, pred.fun = yhat, J = 3, K = 500, NA.plot = TRUE

)

ALE.4 <- ALEPlot(

DAT[,2:5], nnet.DAT, pred.fun = yhat, J = 4, K = 500, NA.plot = TRUE

)

In the {ALEPlot} implementation, calling the function

automatically prints a plot. While this provides some convenience if

that is what the user wants, it is not so convenient if the user does

not want to print a plot at the very point of ALE creation. It is

particularly inconvenient for script building. Although it is possible

to configure R to suspend graphic output before the

{ALEPlot} is called and then restart it after the function

call, this is not so straightforward—the function itself does not give

any option to control this behaviour.

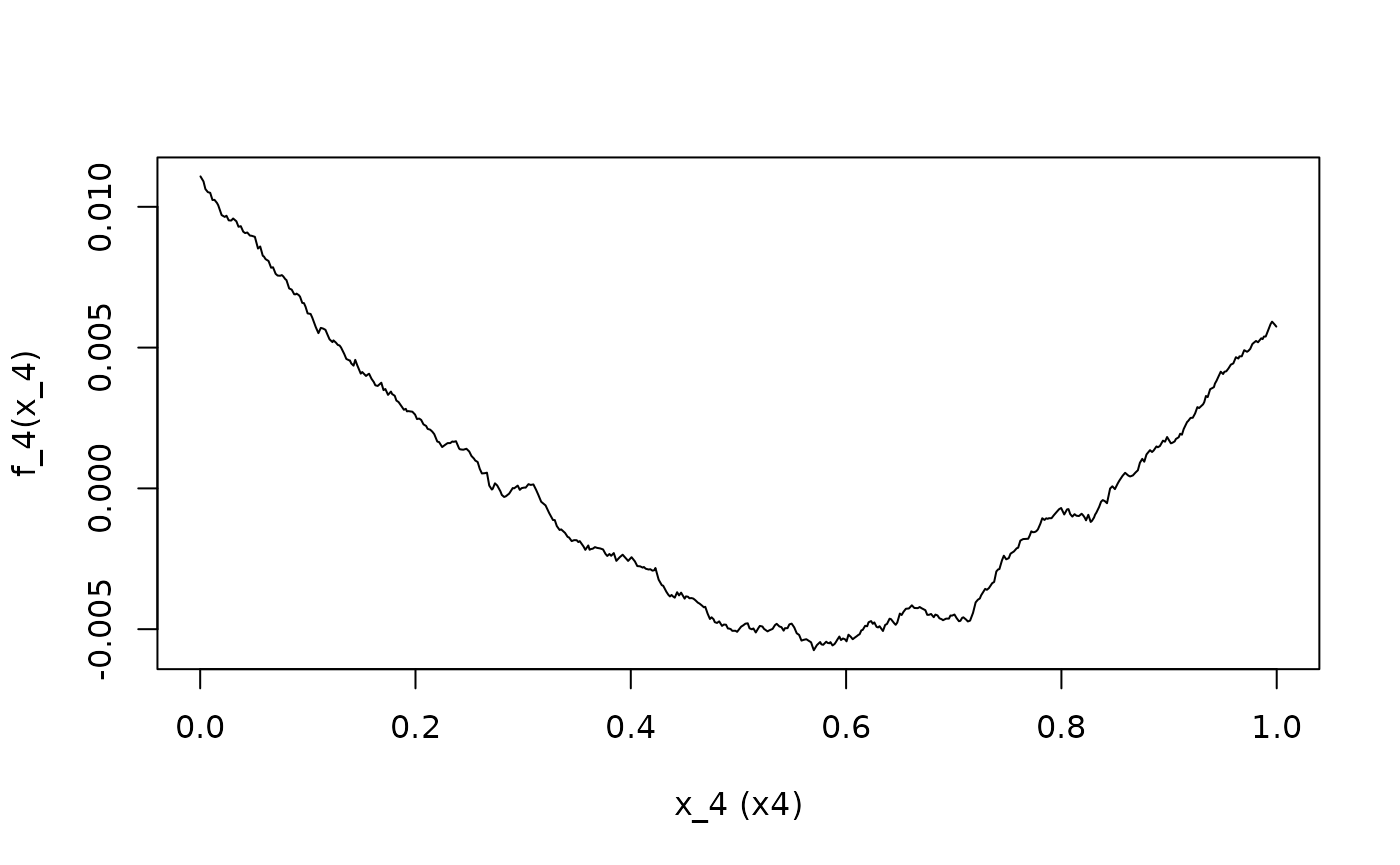

ALE interactions can also be calculated and plotted:

## Calculate and plot the ALE second-order effects of {x1, x2} and {x1, x4}

ALE.12 <- ALEPlot(

DAT[,2:5], nnet.DAT, pred.fun = yhat, J = c(1,2), K = 100, NA.plot = TRUE

)

If the output of the {ALEPlot} has been saved to

variables, then its contents can be plotted with finer user control

using the generic R plot method:

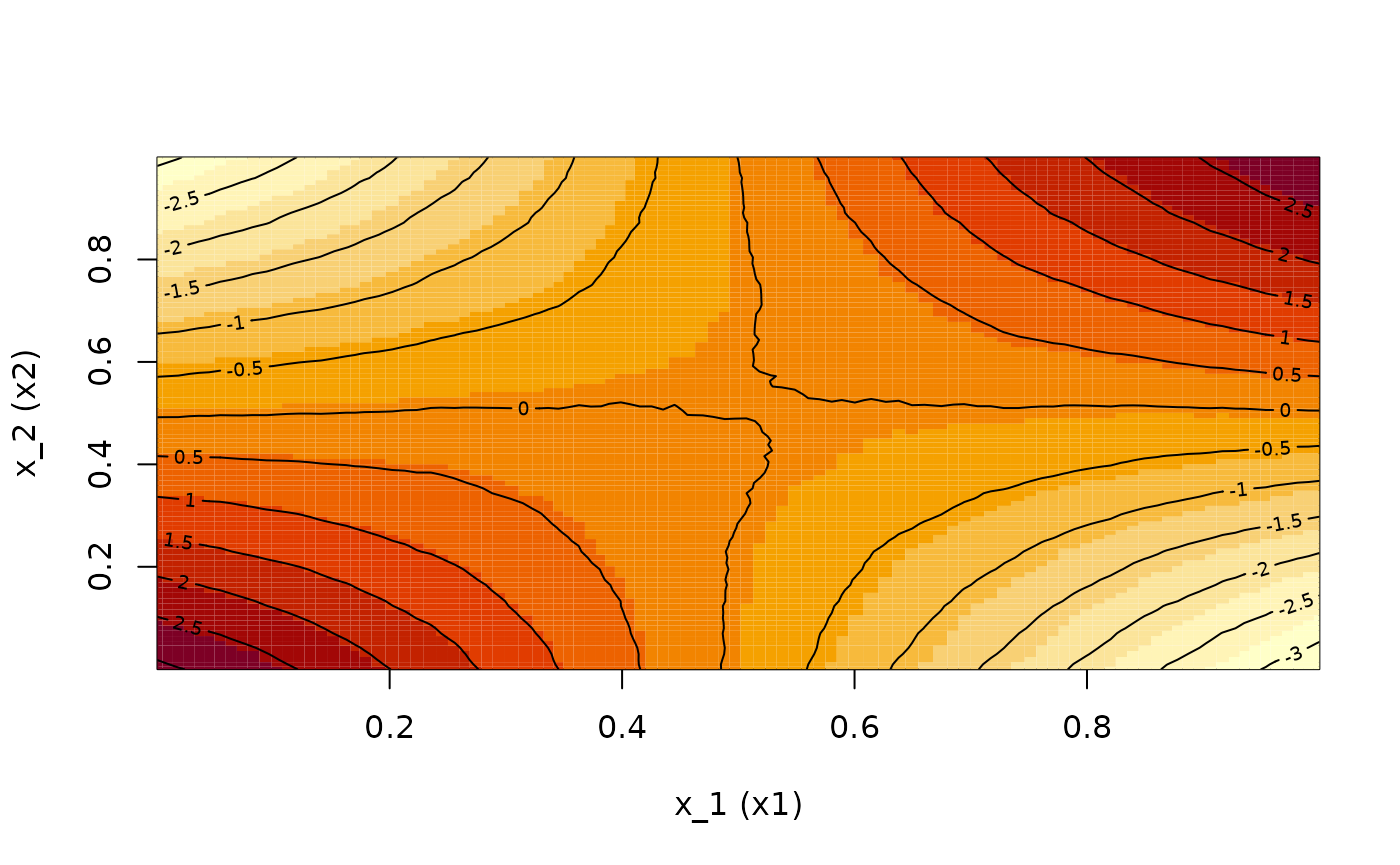

## Manually plot the ALE main effects on the same scale for easier comparison

## of the relative importance of the four predictor variables

par(mfrow = c(3,2))

plot(

ALE.1$x.values, ALE.1$f.values, type="l", xlab="x1",

ylab="ALE_main_x1", xlim = c(0,1), ylim = c(-2,2), main = "(a)"

)

plot(

ALE.2$x.values, ALE.2$f.values, type="l", xlab="x2",

ylab="ALE_main_x2", xlim = c(0,1), ylim = c(-2,2), main = "(b)"

)

plot(

ALE.3$x.values, ALE.3$f.values, type="l", xlab="x3",

ylab="ALE_main_x3", xlim = c(0,1), ylim = c(-2,2), main = "(c)"

)

plot(

ALE.4$x.values, ALE.4$f.values, type="l", xlab="x4",

ylab="ALE_main_x4", xlim = c(0,1), ylim = c(-2,2), main = "(d)"

)

## Manually plot the ALE second-order effects of {x1, x2} and {x1, x4}

image(

ALE.12$x.values[[1]], ALE.12$x.values[[2]], ALE.12$f.values, xlab = "x1",

ylab = "x2", main = "(e)"

)

contour(

ALE.12$x.values[[1]], ALE.12$x.values[[2]], ALE.12$f.values, add=TRUE,

drawlabels=TRUE

)

image(

ALE.14$x.values[[1]], ALE.14$x.values[[2]], ALE.14$f.values, xlab = "x1",

ylab = "x4", main = "(f)"

)

contour(

ALE.14$x.values[[1]], ALE.14$x.values[[2]], ALE.14$f.values, add=TRUE,

drawlabels=TRUE

)

ale package equivalent

Now we demonstrate the same functionality with the ale

package. We will work with the same model on the same data, so we will

not create them again.

To create the model, we invoke the ALE() constructor

which returns an ALE S7 object:

library(ale)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'ale'

#> The following object is masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> get

nn_ale <- ALE(

nnet.DAT,

data = DAT,

pred_type = "raw",

p_values = NULL

)Here are some notable differences compared to

ALEPlot:

- Unlike

{ALEPlot}that functions on only one variable at a time,alegenerates ALE data for multiple variables in a dataset at once. By default, it generates ALE elements for all the individual predictor variables in the dataset that it is given (“first order” or 1D ALE); the user can specify a single variable or any subset of variables. We will cover more details in another vignette, but for our purposes here, we note theget()method can subsequently retrieve ALE data or plots for specific variables. - The

ALE()constructor creates a default generic predict function that matches most standard R models. When the prediction type is not the default “response”, as in our case, the user can set the desired type with thepred_typeargument. However, for more complex or non-standard prediction functions,alesupports custom functions with thepred_funargument. Seehelp(ALE)for details.

The plots can easily be printed out all at once by calling the

plot() method. This generates an S7

ALEPlots object that contains all possible plots from the

ALE data, along with convenient plot(),

print(), and other methods. Simply calling

plot() on the ALE object plots all the ALE

plots together:

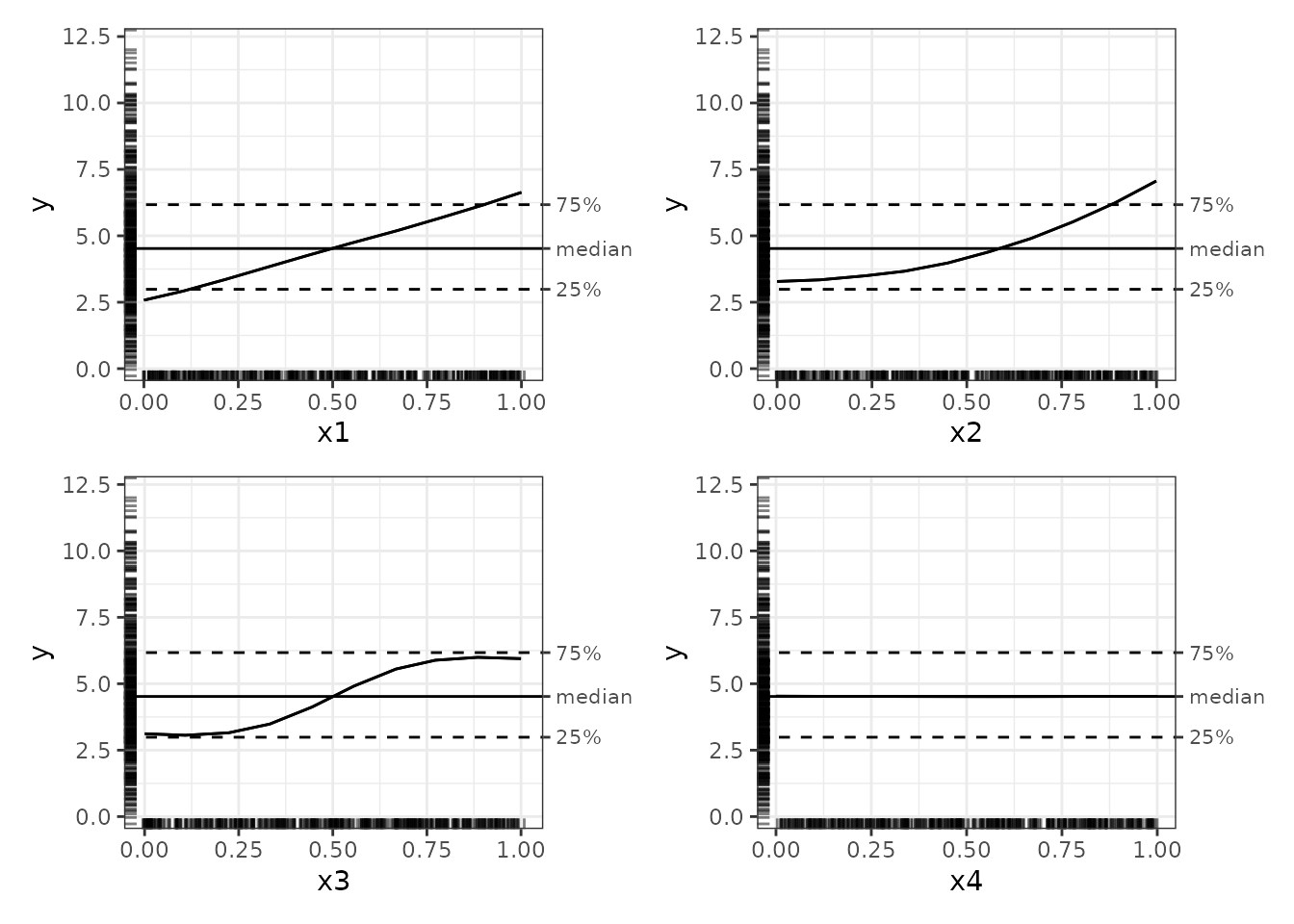

# Print plots

plot(nn_ale)

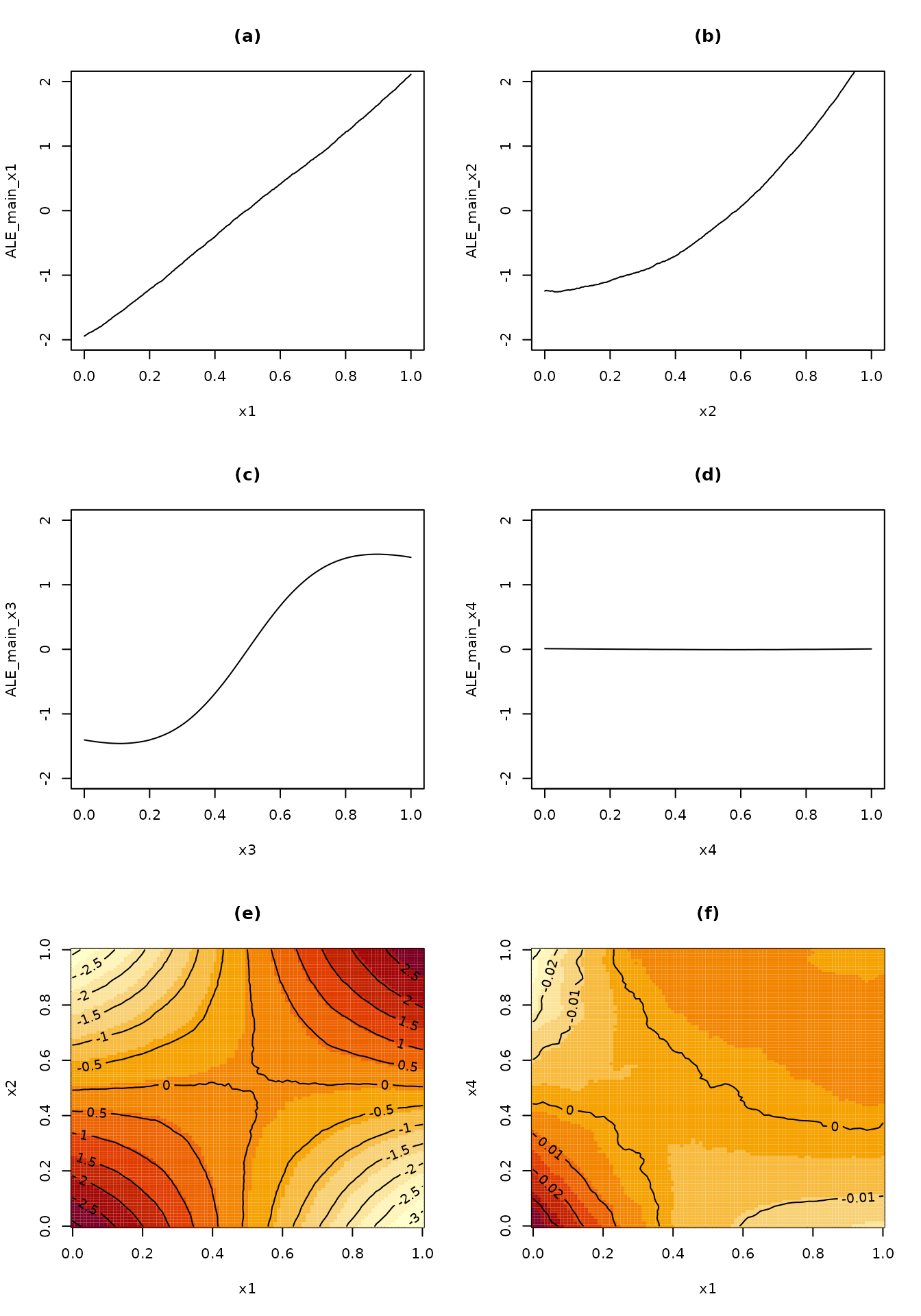

The plots in the ale package have numerous features that

enhance interpretability:

- The outcome y is displayed on its full original scale for context.

- By default, plots are centred on the median, which is more intuitive

than zero-centring because it is easier to see the effects of a variable

relative to typical values. They can be centred on zero or on the mean

with the

ale_centreargument. - The 25% and 75% percentile markers show the middle 50% of the y values. Any ALE y value beyond these bands indicates that the x variable is so strong that it alone at the values indicated can shift the y value by that much.

- Rug plots indicate the distribution of the data so that outliers are not over-interpreted.

It might not be clear that the previous plots display exactly the

same data as those shown above from ALEPlot. To make the

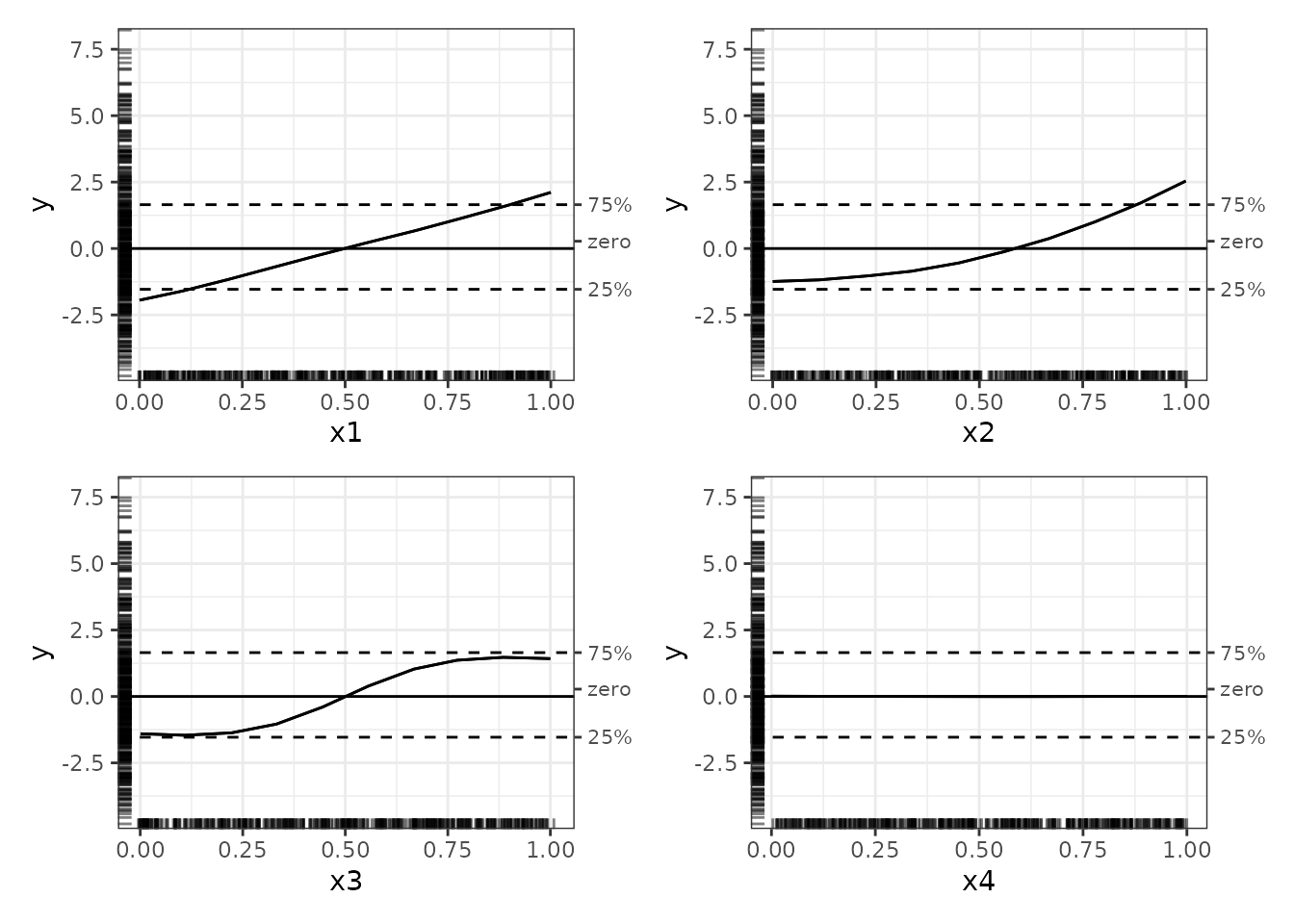

comparison clearer, we can plot the ALEs on a zero-centred scale:

# Zero-centred ALE plots

plot(nn_ale, ale_centre = 'zero')

With these zero-centred plots, the full range of y values and the rug plots give some context that aids interpretation. (If the rugs look slightly different in each plot, it is because they are randomly jittered to avoid overplotting.)

The ale package also produces interaction plots; see the

introductory

vignette for details on how they are specified and created.

# Create and plot interactions

nn_ale_2D <- ALE(

model = nnet.DAT,

x_cols = list(d2 = TRUE),

data = DAT,

pred_type = "raw",

p_values = NULL

)

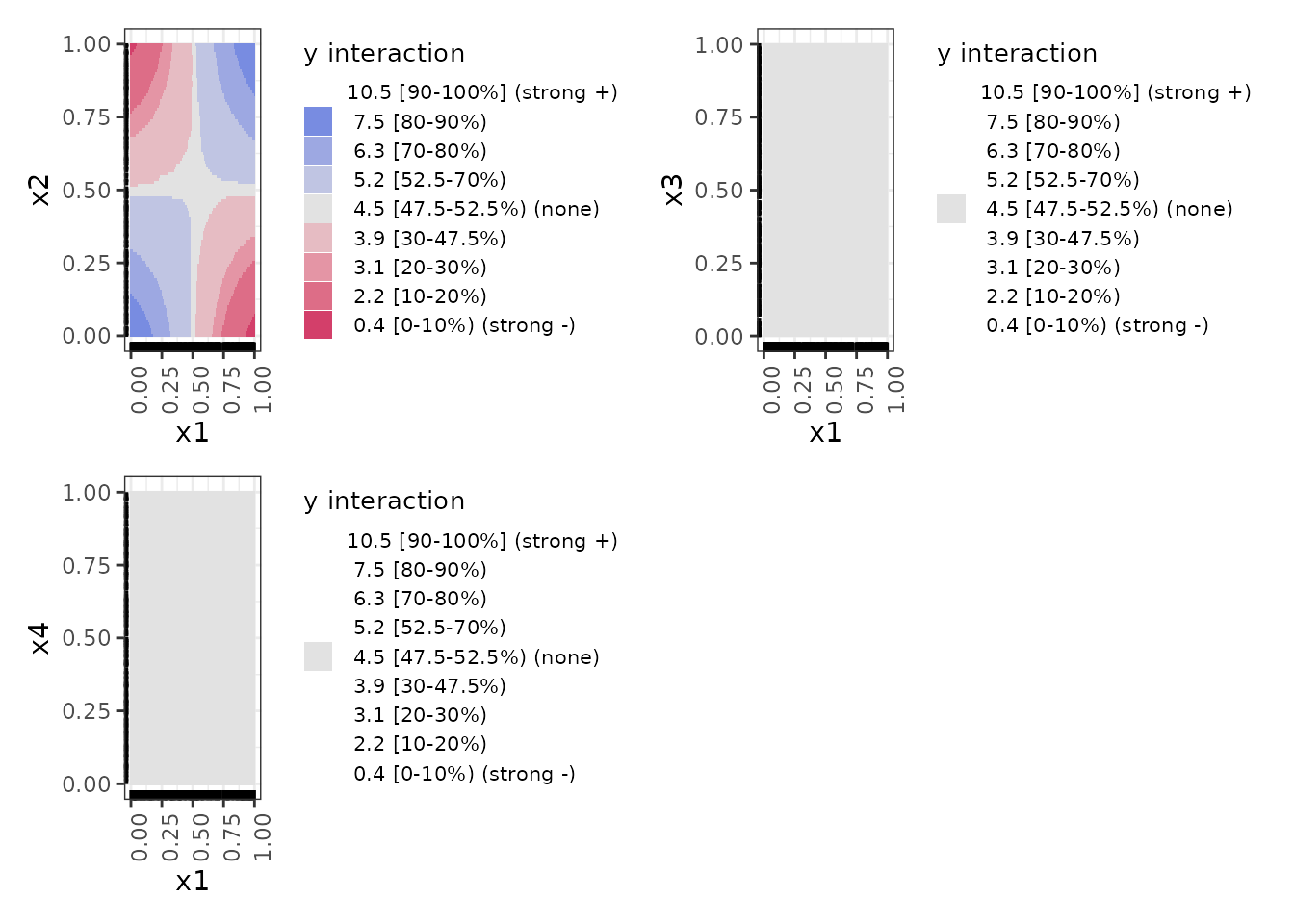

# Print plots: plot() creates ALL possible plots from an ALE object

nnet_plots <- plot(nn_ale_2D)

print(nnet_plots, ncol = 2)

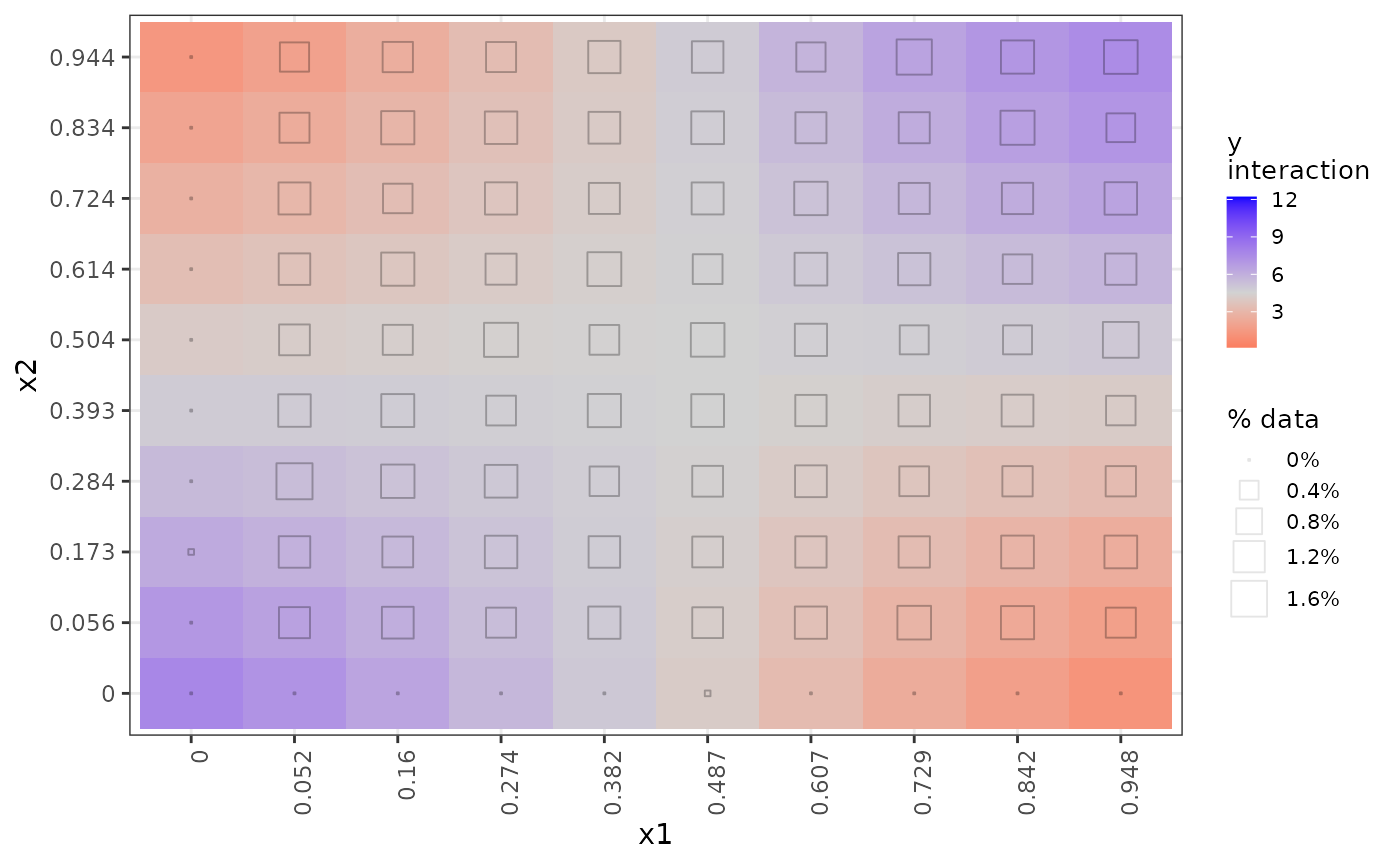

Here is a close-up of the x1 by x2

interaction plot:

# get() retrieves a specific desired plot

get(nnet_plots, 'x1:x2')

These interaction plots are heat maps that indicate the interaction

regions that are above or below the average value of y with

colour-blind–friendly colours on a diverging gradient. Blue indicates a

positive interaction effect relative to the median; grey indicates no

meaningful interaction; red indicates a negative effect. We find these

easier to interpret than the contour maps from ALEPlot,

especially since the colours in each plot are on the same scale and so

the plots are directly comparable with each other. (The colour scheme is

somewhat different when ALE statistics with p-values are calculated and

plotted, which we do not present in this vignette.)

Rather than rug plots, the frequency of data in each interaction cell is indicated by a hollow square whose size varies with the percentage of data represented in the respective cell, as the legend “% data% indicates. In this synthetic dataset, most of the cells are equally represented with around 1.2% of the data; only the border cases have little or no data. This indication of data frequency is much more useful on real datasets as we have below where there are stark disparities in data representation in interaction cells.

The interpretation of these interaction plots is that in any given

region, the interaction between x1 and x2

increases (blue) or decreases (red) y by the amount indicated

over and above the separate individual direct effects of x1

and x2 shown in the 1D ALE plots above. It is

not an indication of the total effect of both variables

together but rather of the additional effect of their interaction beyond

their individual effects. Thus, only the x1-x2 interaction

shows any effect. For the interactions with x3, even though

x3 indeed has a strong effect on y as we see in

the 1D ALE plot above, it has no additional effect in interaction with

the other variables, and so its interaction plots are entirely grey.

Real data with binary outcomes (ALEPlot Example 3)

The next code example from the {ALEPlot} package

analyzes a real dataset with a binary outcome variable. Whereas the

{ALEPlot} has the user load a CSV file that might not be

readily available, we make that dataset available as the census dataset.

We load it here with the adjustments necessary to run the

{ALEPlot} example.

## R code for Example 3

## Load relevant packages

library(ALEPlot)

library(gbm, quietly = TRUE)

#> Loaded gbm 2.2.2

#> This version of gbm is no longer under development. Consider transitioning to gbm3, https://github.com/gbm-developers/gbm3

## Read data and fit a boosted tree supervised learning model

data(census, package = 'ale') # load ale package version of the data

data <-

census |>

as.data.frame() |> # ALEPlot is not compatible with the tibble format

select(age:native_country, higher_income) |> # Rearrange columns to match ALEPlot order

stats::na.omit(data)Although gradient boosted trees generally perform quite well, they

are rather slow. So, we train this tree with only 600 trees rather than

the 6000 from the original demo. Note that the model calls is based on

data[,-c(3,4)], which drops the third and fourth variables

(fnlwgt and education, respectively).

# Note: GBM training is rather slow

set.seed(0)

gbm.data <- gbm(

higher_income ~ .,

data = data[,-c(3,4)] |>

# gbm::gbm() requires binary response outcomes to be numeric 0 or 1

mutate(higher_income = as.integer(higher_income)),

distribution = "bernoulli",

# the original demo trained 6000 trees; it is reduced here to 600 to be faster

n.trees=600,

shrinkage=0.02,

interaction.depth=3

)

gbm.data

#> gbm(formula = higher_income ~ ., distribution = "bernoulli",

#> data = mutate(data[, -c(3, 4)], higher_income = as.integer(higher_income)),

#> n.trees = 600, interaction.depth = 3, shrinkage = 0.02)

#> A gradient boosted model with bernoulli loss function.

#> 600 iterations were performed.

#> There were 12 predictors of which 12 had non-zero influence.ALEPlot code

As before, we create a custom prediction function and then call the

{ALEPlot} function to generate the plots. The prediction

type here is “link”, which represents the log odds in the

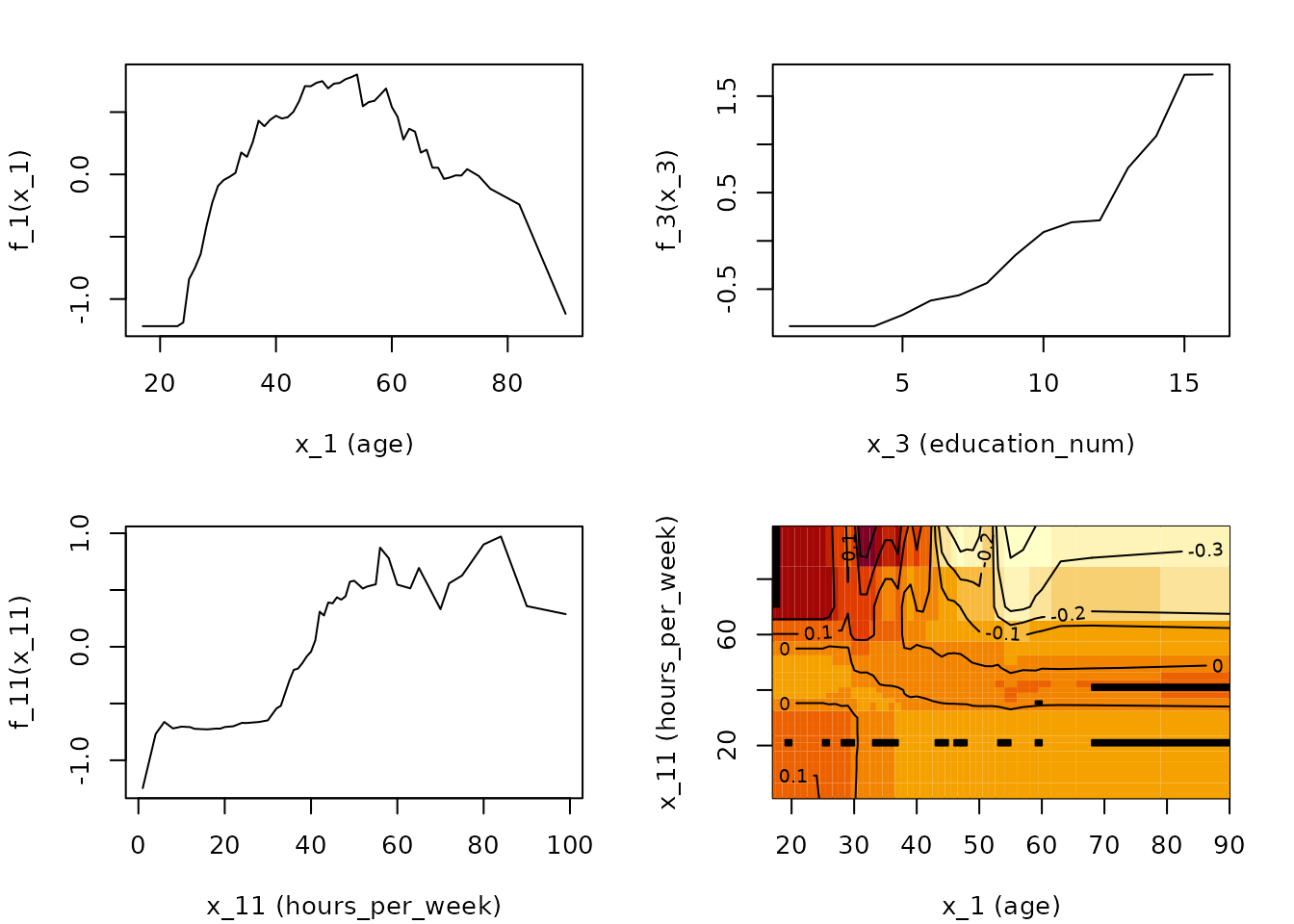

gbm package.

Creation of the ALE plots here is rather slow because the

gbm predict function is slow. In this example, only

age, education_num (number of years of

education), and hours_per_week are plotted, along with the

interaction between age and

hours_per_week.

# Define the predictive function; note the additional arguments for the

# predict function in gbm.

yhat <- function(X.model, newdata) as.numeric(predict(

X.model, newdata, n.trees = 600, type="link"

))

# Calculate and plot the ALE main and interaction effects for x_1, x_3,

# x_11, and {x_1, x_11}

par(mfrow = c(2,2), mar = c(4,4,2,2)+ 0.1)

ALE.1 <- ALEPlot(

data[,-c(3,4,15)], gbm.data, pred.fun=yhat, J=1, K=100, NA.plot = TRUE

)

ALE.3 <- ALEPlot(

data[,-c(3,4,15)], gbm.data, pred.fun=yhat, J=3, K=100, NA.plot = TRUE

)

ALE.11 <- ALEPlot(

data[,-c(3,4,15)], gbm.data, pred.fun=yhat, J=11, K=100, NA.plot = TRUE

)

ALE.1and11 <- ALEPlot(

data[,-c(3,4,15)], gbm.data, pred.fun=yhat, J=c(1,11), K=50, NA.plot = FALSE

)

ale package equivalent

Here is the analogous code using the ale package. In

this case, we also need to define a custom predict function because of

the particular n.trees argument. To speed things up in this

vignette, we train only 600 trees rather than the 6000 from the original

{ALEPlot} demonstration.

Log odds

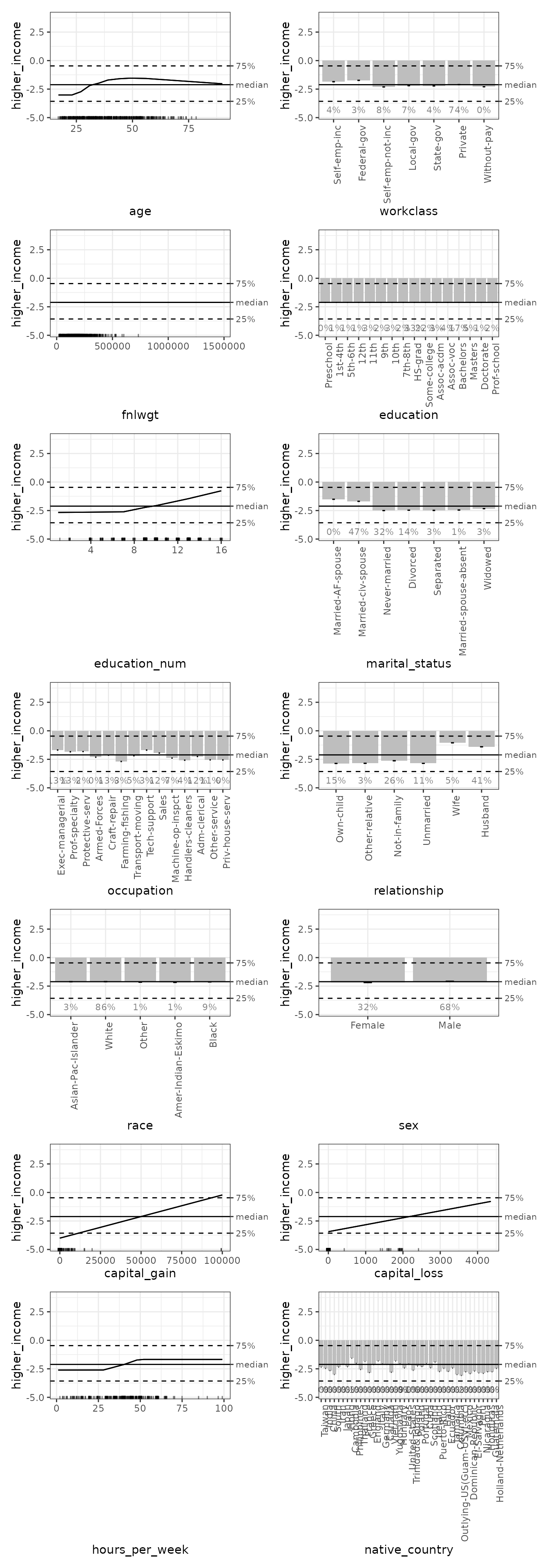

We generate ALE for all 1D variables and for all 2D interactions

involving age. However, we focus on age,

education_num, and hours_per_week for

comparison with {ALEPlot}. If the shapes of these plots

look different, it is because ale tries as much as possible

to display plots on the same y-axis coordinate scale for easy comparison

across plots.

# Custom predict function that returns log odds

yhat_link <- function(object, newdata, type) {

predict(object, newdata, type='link', n.trees = 600) |> # return log odds

as.numeric()

}

# Dump plots automatically generated by gbm into a temp PDF file so they don't print

pdf(file = NULL)

# Generate ALE data for all variables and age interactions.

# Note: this is rather slow because there are so many variables.

# However, the built-in parallelization speeds things up quite a bit.

gbm_ale_link <- ALE(

gbm.data,

x_cols = list(

d1 = TRUE, # all 1D ALE effects

d2_all = 'age' # only 2D interactions involving age

),

data = data,

pred_fun = yhat_link,

# Use fewer ALE bins so that interaction plots are easier to interpret

max_num_bins = 10,

p_values = NULL

)

# Return to regular printing of plots

dev.off() |> invisible()

# Create an ALEPlots object with plots for all ALE data from the ALE object

gbm_link_plots <- plot(gbm_ale_link)

# Print only 1D ALE plots

gbm_link_plots |>

# Use subset() instead of get() to keep the special ALEPlots object

# plot and print functionality

subset(list(d1 = TRUE)) |> # 1D plots only

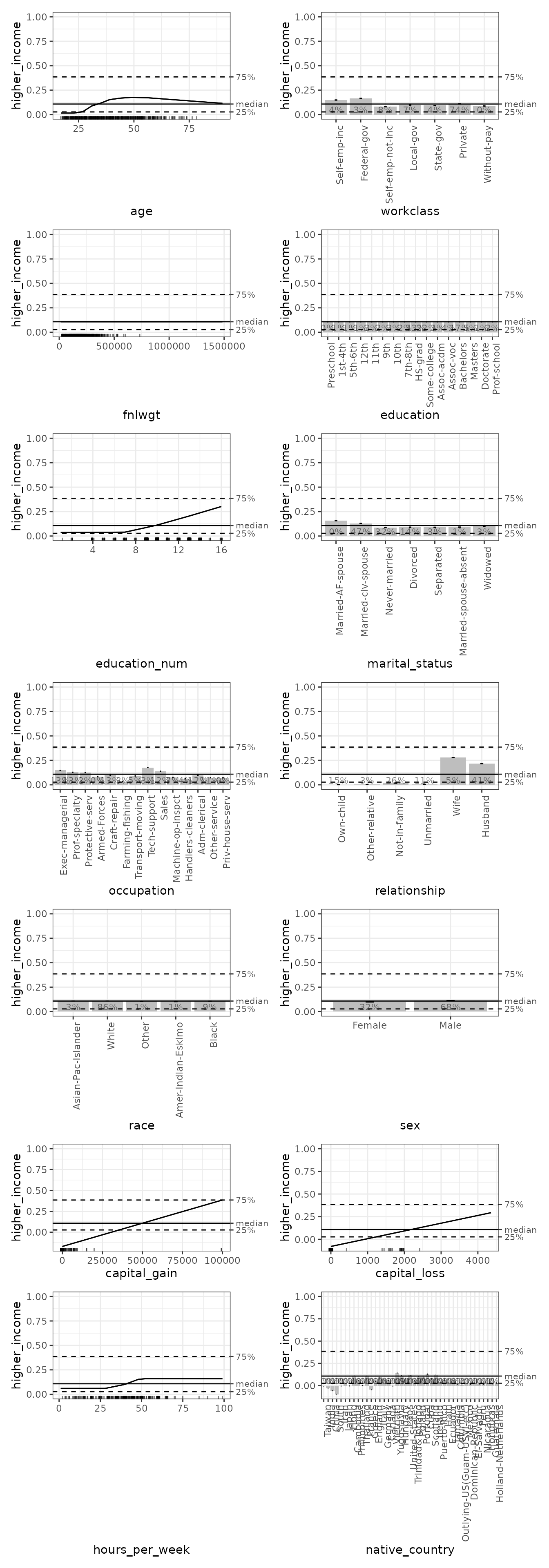

print(ncol = 2) # print in 2 columns

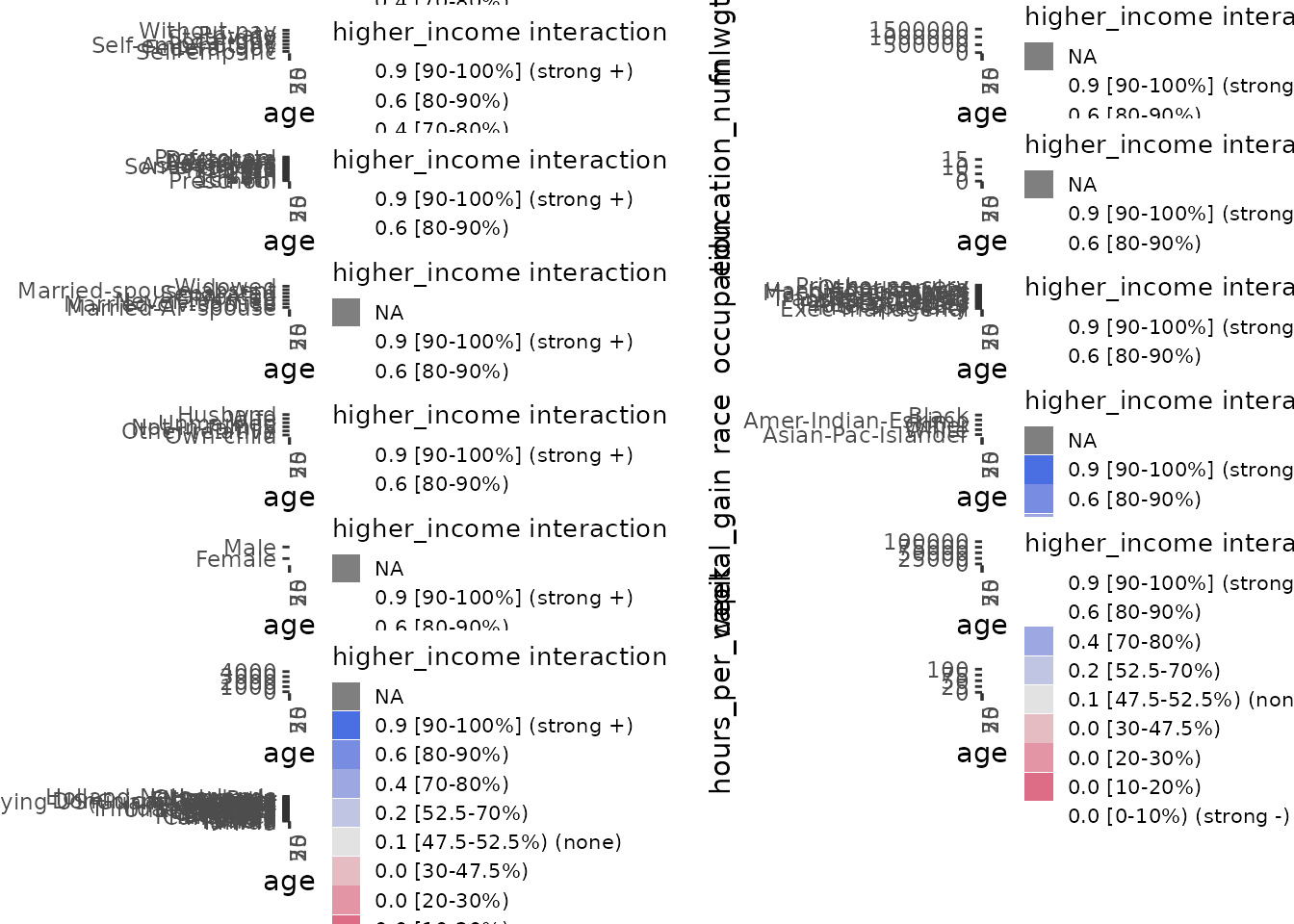

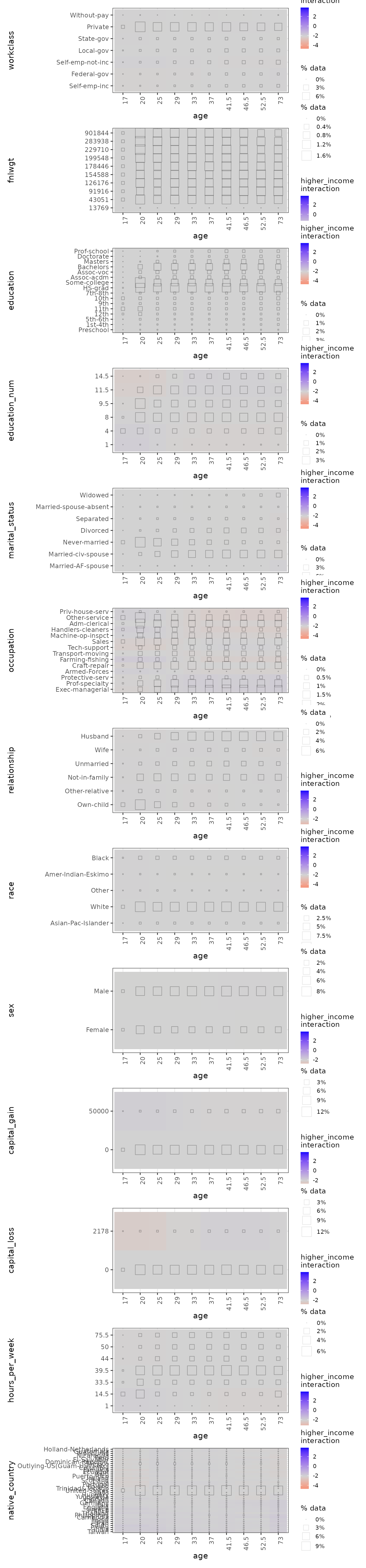

Now we plot all the 2D interactions involving age:

# Print only 2D ALE plots involving age

gbm_link_plots |>

# Use subset() instead of get() to keep the special ALEPlots object

# plot and print functionality

subset(list(d2_all = 'age')) |>

print(ncol = 1) # print in 1 column

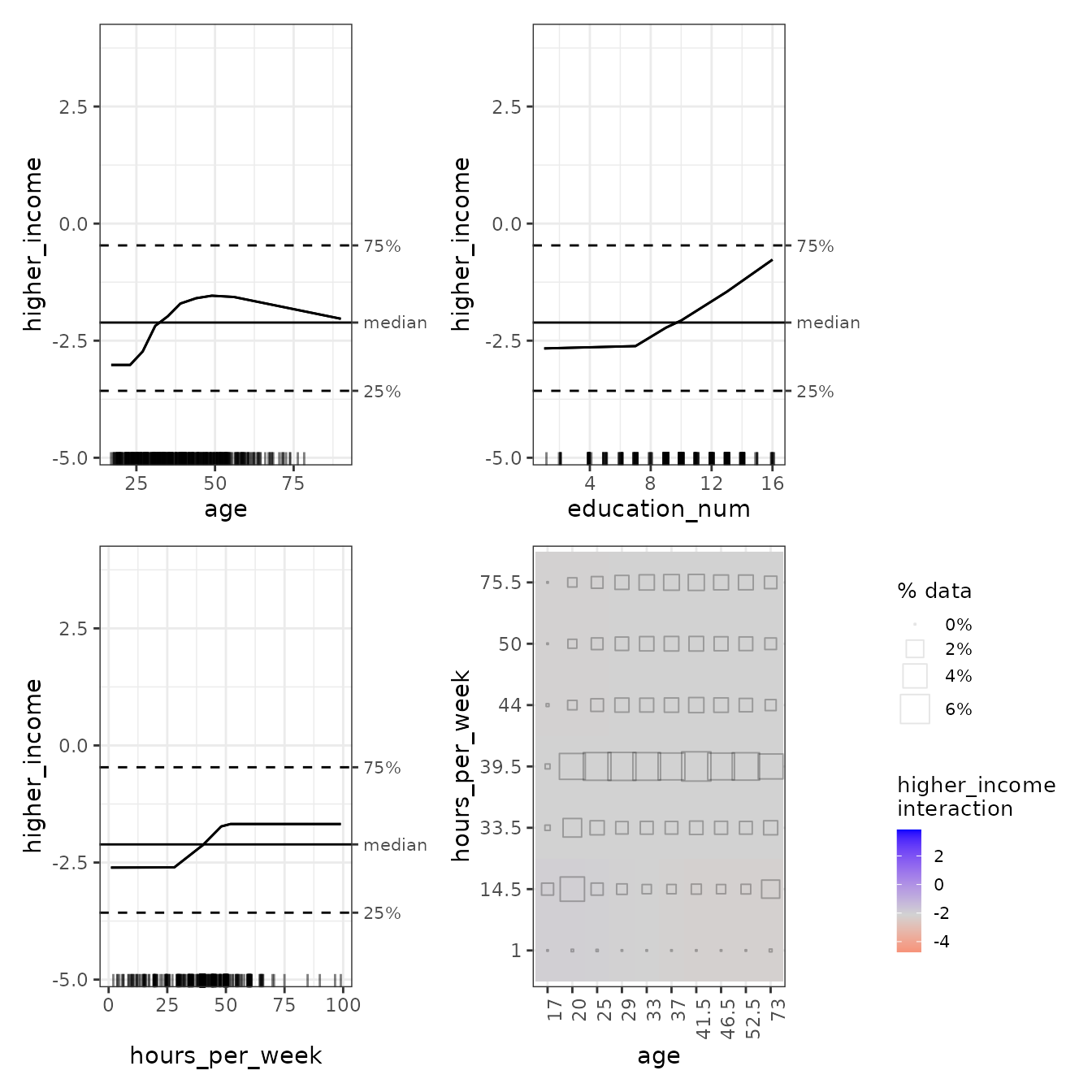

For direct comparison with {ALEPlot}, we can select the

1D plots for age, education_num, and

hours_per_week, with the age-hours_per_week

interaction. If the shapes of these plots look different, it is because

ale tries as much as possible to display plots on the same

y-axis coordinate scale for easy comparison across plots:

# Print only 2D ALE plots involving age

gbm_link_plots |>

# Use subset() instead of get() to keep the special ALEPlots object

# plot and print functionality

get(~ age + education_num + hours_per_week + age:hours_per_week) |>

purrr::list_flatten() |>

patchwork::wrap_plots()

In the age:hours_per_week interaction plot, we can see

that the interactions, if existent, are very week. The consistent-colour

coding of the ale package makes this much clearer than the

{ALEPlot} package.

Predicted probabilities

Log odds are not necessarily the most interpretable way to express probabilities (though we will show shortly that they are sometimes uniquely valuable). So, we repeat the ALE creation using the “response” prediction type for probabilities and the default median centring of the plots.

As we can see, the shapes of the plots are similar, but the y-axes are more easily interpretable as the probability (from 0 to 1) that a census respondent is in the higher income category. The median of around 10% or so indicates the median prediction of the GBM model: half of the respondents were predicted to have higher than a 10% likelihood of being higher income and half were predicted to have lower likelihood. The y-axis rug plots indicate that the GBM model predictions were generally rather extreme, either relatively close to 0 or 1, with few predictions in the middle.

# Custom predict function that returns probabilities

yhat_probs <- function(object, newdata, type) {

predict(

object, newdata, type = "response", # return predicted probabilities

n.trees = 600

) |> # return log odds

as.numeric()

}

# Dump plots automatically generated by gbm into a temp PDF file so they don't print

pdf(file = NULL)

# Generate ALE data for all variables and age interactions.

# Note: this is rather slow because there are so many variables.

# However, the built-in parallelization speeds things up quite a bit.

gbm_ale_probs <- ALE(

gbm.data,

x_cols = list(

d1 = TRUE, # all 1D ALE effects

d2_all = 'age' # only 2D interactions involving age

),

data = data,

pred_fun = yhat_probs,

# Use fewer ALE bins so that interaction plots are easier to interpret

max_num_bins = 10,

p_values = NULL

)

# Return to regular printing of plots

dev.off() |> invisible()

# Create ALEPlots object with plots for all ALE data from the ALE object

gbm_probs_plots <- plot(gbm_ale_probs)

# Print only 1D ALE plots

gbm_probs_plots |>

# Use subset() instead of get() to keep the special ALEPlots object

# plot and print functionality

subset(list(d1 = TRUE)) |> # 1D plots only

print(ncol = 2) # print in 2 columns

Finally, we again generate 2D interactions, this time based on probabilities instead of on log odds. However, probabilities might not be the best choice for indicating interactions because, as we see from the rugs in the 1D ALE plots, the GBM model heavily concentrates its probabilities in the extremes near 0 and 1. Thus, the plots’ suggestions of strong interactions are likely exaggerated. In this case, the log odds ALEs shown above are probably more relevant.

# Print only 2D ALE plots involving age

gbm_probs_plots |>

# Use subset() instead of get() to keep the special ALEPlots object

# plot and print functionality

subset(list(d2_all = 'age')) |>

print(ncol = 1) # print in 1 column